Nearly every GP practice in England is now using digital tools to manage their populations, and with the new GP contract for 2025/2026 mandating online access, we've crossed the Rubicon. There's no going back.

But here's the troubling question: as we embrace this digital future, are we inadvertently leaving our most vulnerable patients behind?

We're witnessing a seismic shift in how primary care operates. The 10-year plan is moving neighbourhood healthcare from strategy to reality, asking practices to embed genuine population health approaches into everything they do (1). Meanwhile, outcome-based contracts loom on the horizon - where payment will follow patient outcomes, not just activity levels.

This is actually welcome news for primary care. We're already familiar with outcome-based thinking through our block contracts, where one visit per year pays the same as 100 (with only the flawed Carr Hill formula attempting to balance this out). The new contracts could finally address this longstanding issue. But as we pivot towards population health management, we must confront an uncomfortable truth about digital exclusion.

Consider patients with serious mental illness (SMI). NICE guidelines and QOF incentives drive us to review these patients annually - not just for their mental health, but crucially for their cardiovascular risk. The data backing this approach is stark: SMI patients are five times more likely to die prematurely than those without these conditions (2).

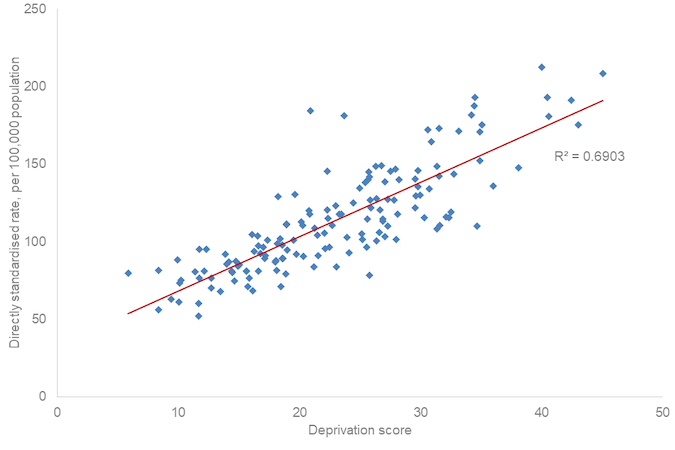

What's even more sobering is the linear relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and risk. The more deprived the area, the higher the premature mortality rate for SMI patients. It's a brutal reminder that health inequalities aren't just statistics - they're life and death realities.

The Marmot Review's "Fair Society, Healthy Lives" from 2008 identified reducing health inequalities as fundamental to a fair society (3). Unsurprisingly, it remains a cornerstone of the future NHS vision. But here's where digital transformation creates both opportunity and risk.

The Good Things Foundation defines digital inclusion as "being able to access the internet and engage online - safely and confidently - when you need and want to" (4). Simple enough. If you can navigate online tools confidently, you'll thrive in the new world of digital primary care.

But what about those who can't? Digital exclusion doesn't occur in isolation - it intersects powerfully with age, poverty, and deprivation. The very populations most at risk of poor health outcomes are often those least equipped to engage with digital healthcare solutions.

This creates a perverse irony: the tools designed to improve population health could actually widen the inequalities they're meant to address.

At Suvera, we grapple with this challenge daily. Our role as a virtual care service isn't just to provide care - it's to ensure we don't exacerbate health inequalities in the process. We do this through data and, crucially, by focusing on who isn't engaging with our service.

While our active patients play a vital role in guiding service development (and we're grateful for their input), it's the silent voices - those who don't engage - that often tell the most important story about equity and access.

Let's think about patients with hypertension. Many patients we reach out to engage confidently with our service. Others need telephone support from our care coordinators to understand the process. But some patients don't engage with us at all.

The easy path would be to stop there - pass these cases back to the practice and move on to the next cohort. But at Suvera, we start conversations, not handoffs.

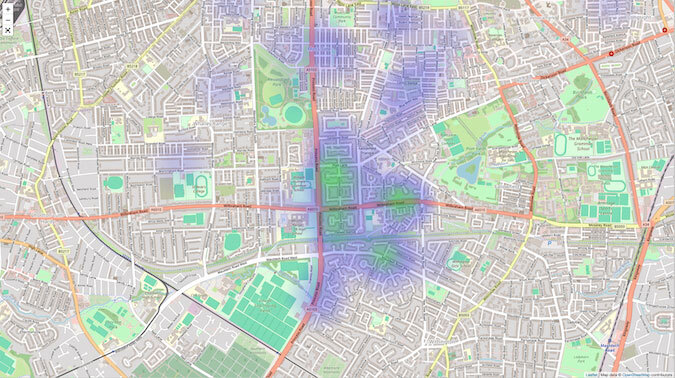

We dig deeper into the data on non-engaging patient cohorts, working with practices to understand what support they need. Population visualisation becomes our secret weapon - overlaying deprivation factors like fuel poverty or CORE20 populations creates a powerful picture that enables meaningful conversations about next steps.

A recent example from a non-engaging hypertension cohort illustrates this perfectly. Rather than writing off these patients, we mapped their characteristics and locations, then planned targeted outreach and community engagement strategies to reduce health inequality.

This is the essence of true neighbourhood care: understanding how our population accesses services and creating opportunities for care that ensure no one gets left behind. It’s what has driven the creation of our free patient health management and recall software to help practices streamline engagement, recall and understanding.

So how do digital tools address health inequalities? Not by assuming everyone can or will engage with them, but by shining a light on those who don't - and bringing their voices into service planning and delivery.

The digital transformation of primary care is inevitable and, in many ways, beneficial. But its true success won't be measured by how efficiently it serves those already comfortable with technology. It will be judged by how well it identifies, understands, and ultimately includes those who risk being left behind.

In a world increasingly driven by digital solutions, our greatest innovation might just be remembering to look for the people the data doesn't capture - and finding new ways to reach them.